‘Could’ is the key word here, as there are a number of reasons why even without rounding Fernando de Noronha, teams will still be heading that way rather than cutting the corner.

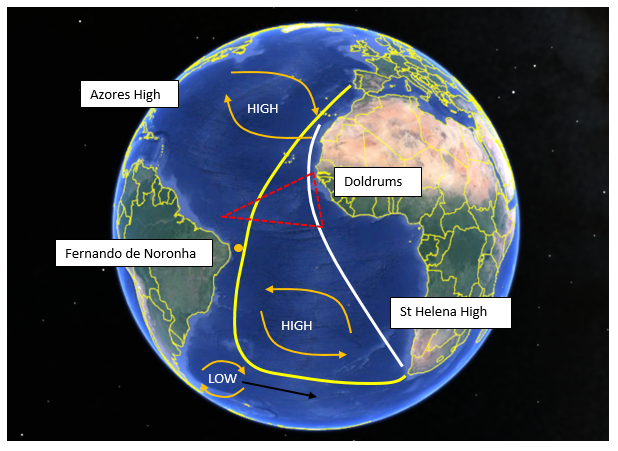

The classic route (shown above in yellow) covers over 1500 nm more, in distance, than what is drawn on as the shorter, more easterly route (shown in white). However, you can also see from this simple schematic some of the large scale weather features that determine the route.

The classic route sets you up in the southern hemisphere with a lot more miles to do, but those miles are all offwind either at your fastest angle or just going fast offwind riding a low pressure system in the southern Atlantic towards the finish. When you can average the same or a little more than wind speed for your boat speed you soon start munching up the miles.

Meanwhile the’ cut the corner’ route will be plodding its way upwind from the Doldrums making for pretty poor VMG. Of the 50 plus routes I calculated with historical data, only 3 routes had the inside corner just ahead or within shouting distance of the classic westerly curve. So you can’t rule it out and I would love to see it but you would be a brave (or foolish) team who takes that on. No one likes going upwind, least of all for 2000+ nm!

Negotiating the weather

Azores High

Typically the Azores high will be sitting off the coast of Portugal, providing a downwind charge towards the equator and setting up a decent NE wind – known as the trade winds. This will allow the boats to charge quickly down towards the Doldrums.

Some acceleration zones can be found around the Canary Islands and the coast of Africa and also around the Cape Verde Islands. Choosing the route through these islands can often be tricky but also quite profitable.

The Doldrums

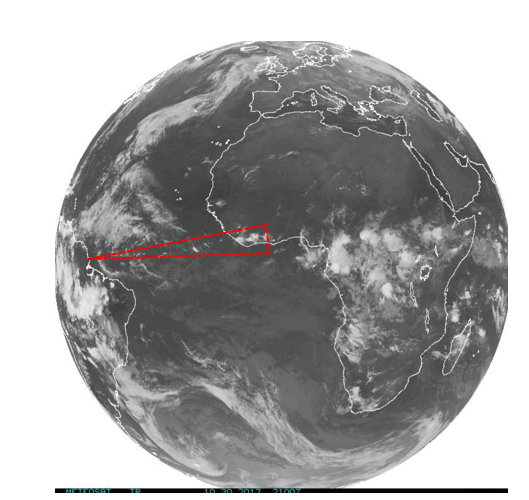

From the schematic earlier you can see a dotted red triangle which indicates crudely where the Doldrums sit. Known also as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), this area is an uneven band of low pressure, creating deeply unstable conditions in a very slack airflow and therefore large shower clouds that move very slowly. You can see from the schematic that their effect lessens the further west you go, a strategy that will be in every navigators head.

Typically, getting west has always been a key goal on this leg in order to reduce the distance you have to traverse in the doldrums. A metre can mean a mile in the tricky cloud driven conditions. With this leg starting almost a month later than the previous year the opportunity to traverse the Doldrums further east than the usual 26-27deg W becomes more of an option and this is where we will start to see differences in the fleet setup as they take on cloud dodging. Regularly monitoring the cloud activity in the Doldrums and trying to identify any consistency in width of the zone will help teams determine their approach.

Then it will be Radar at the ready to spot the clouds that will make or break them.